PCB acts as the carrier for many components and as the hub for circuit signal transfer. It has become a very important and key part of electronic information products. The quality and reliability level of the PCB decide the quality and reliability of the whole device.

With the miniaturization of electronic information products and the push for lead-free and halogen-free environmental rules, PCBs have moved toward higher density, higher Tg, and more eco-friendly materials. But because of cost and technology limits, many failures occur during PCB manufacturing and use. These failures cause many quality disputes. To find why failures happen, to find ways to fix them, and to sort out responsibility, it is necessary to carry out failure analysis for the failures that occur.

Basic steps in failure analysis

To get the accurate cause or mechanism of a PCB failure or defect, basic principles and an analysis flow must be followed. If you do not follow them, you may lose valuable failure information. Analysis may stop or give a wrong conclusion. A common basic flow is as follows.

First, based on the failure symptom, collect information, do functional tests, electrical tests, and simple visual checks. Use these to find the failed area and the failure mode. This is failure localization or fault localization.

For simple PCBs or simple PCBA boards, the failed part is easy to find. But for complex devices or substrates, such as BGA or MCM packages, defects are not easy to see with a microscope. They are hard to find at first. At that time, other methods are needed.

Next, analyze the failure mechanism. Use physical and chemical methods to study the mechanism that led to the PCB failure or defect. These mechanisms may include cold solder joints, contamination, mechanical damage, moisture-induced stress, dielectric corrosion, fatigue damage, CAF or ionic migration, stress overload, and so on.

After that, analyze the root cause of the failure. Based on the failure mechanism and the manufacturing process, look for the reasons that caused the mechanism to happen. If needed, do experiments to verify the cause. You should run test verification whenever possible. Experiments can find the exact cause that led to the failure.

This then gives a clear, targeted basis for the next improvement step. Make the failure analysis report based on the test data, facts, and conclusions from the analysis. The facts must be clear. The logic must be tight. The layout must be orderly. Do not imagine causes without proof.

During analysis, use methods from simple to complex, from outside to inside, and from non-destructive to destructive. Follow these basic rules. Only by doing this can you avoid losing key information and avoid adding new, human-made failure mechanisms.

This is like a traffic accident. If one party destroys the scene or runs away, even a skilled police officer cannot make a correct judgment about responsibility. Traffic law usually requires the party who ran away or who destroyed the scene to bear all responsibility.

The same is true for PCB or PCBA failure analysis. If someone uses a soldering iron to rework a failed solder joint or uses heavy scissors to cut a PCB, later analysis is impossible. The failure scene is destroyed. This is especially bad when there are only a few failed samples. If the failed scene is damaged, the true cause cannot be found.

Failure analysis techniques

Optical microscope

An optical microscope is mainly for visual inspection of the PCB. Use it to find the failed area and related physical evidence. It gives a first judgment of the failure mode. Visual inspection looks for PCB contamination, corrosion, cracked boards, circuit traces, and patterns in failures. For example, check whether failures come in batches or are individual cases. Check whether failures always cluster in one region.

X-ray (X-ray inspection)

For parts that cannot be seen by visual inspection, or for internal defects in through-holes and other inner defects, use an X-ray imaging system. The X-ray system works by the different absorption or transmission of X-rays by materials of different thickness or density. This creates images. People often use X-ray to inspect internal defects in PCBA solder joints, internal defects in through-holes, and to locate defective solder joints in high-density packages like BGA or CSP.

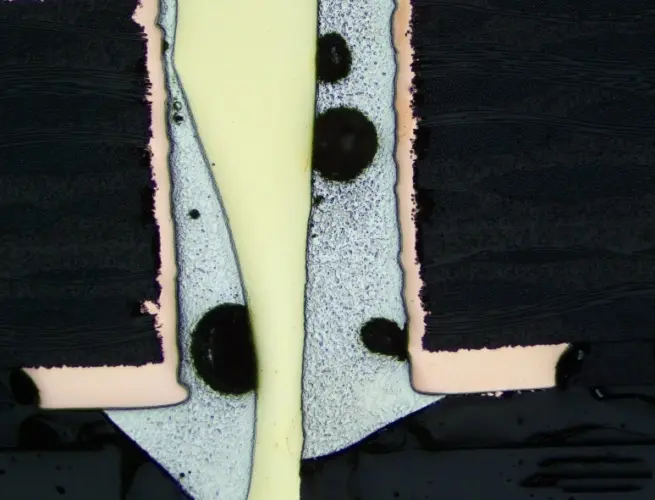

Cross-section analysis

Cross-section analysis means sampling, embedding, slicing, polishing, etching, and observing a PCB cross-section. This process shows the internal structure of the PCB. Through cross-section analysis, you get rich microstructure information about PCB features (such as through-holes and plating). This helps guide quality improvements. But this method is destructive. Once you slice the sample, it is destroyed.

Scanning acoustic microscopy (SAM)

Today, the main tool for packaging and assembly analysis is C-mode scanning acoustic microscopy. It uses high-frequency ultrasound waves. These waves reflect at material discontinuities. The change in amplitude, phase, and polarity is used to form images. The scan moves along the Z axis to record X-Y plane information.

Therefore, SAM can detect many internal defects in components, materials, and PCBs or PCBAs. It finds cracks, delamination, inclusions, and voids. If the SAM frequency range is wide enough, it can also detect internal defects in solder joints.

Typical SAM images use a warning color, such as red, to show defects. During the move from leaded to lead-free SMT processes, many moisture-related reflow issues have appeared. Moisture-absorbed plastic packages can delaminate or crack inside when they are reflowed at the higher temperatures of lead-free processes. Ordinary PCBs can also crack or delaminate at these higher temperatures.

In this case, SAM shows special advantages for non-destructive testing of multilayer, high-density PCBs. Large visible board cracks or blown boards, however, can usually be found by simple visual inspection.

Micro-FTIR (microscale infrared analysis)

Micro-infrared analysis combines infrared spectroscopy with microscopy. It uses the fact that different materials—mainly organic materials—absorb infrared light differently. This way, you can analyze the chemical components of a material. With a microscope, visible light and infrared can share the same light path. Under the visible field, you can find small amounts of organic contamination to analyze.

Without the microscope, infrared spectroscopy usually needs a larger sample amount. In electronic processes, tiny contamination can cause poor solderability of a pad or lead. So without micro-scope-coupled infrared, it is hard to solve some process problems. Micro-FTIR is mainly used to analyze organic contamination on solder surfaces or solder joints and to analyze causes of corrosion or poor solderability.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

A scanning electron microscope is a helpful large imaging system for failure analysis. It is used for morphology observation. Modern SEMs are powerful. They can magnify fine structures or surface features to hundreds of thousands of times.

In PCB or solder joint failure analysis, SEM is mainly for analyzing failure mechanisms. Specifically, SEM is used to observe the surface morphology of pads, the metallographic structure of solder joints, to measure intermetallic compounds, to analyze solderable coatings, and to analyze and measure tin whiskers.

Compared with an optical microscope, an SEM forms an electron image, so it is black and white. SEM samples must be conductive. For nonconductors and some semiconductors, you must coat the sample with gold or carbon. Otherwise, charge will build up on the sample surface and affect observation. SEM images have much greater depth of field than optical microscopes. For metallographic structures, micro fracture surfaces, and tin whiskers, SEM is an important analysis method.

Thermal analysis

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC measures the power difference between a test sample and a reference under program-controlled temperature. It records the relation between power difference and temperature or time. DSC studies how heat changes with temperature. From that, you can study the physical, chemical, and thermodynamic behavior of materials.

DSC has many uses. In PCB analysis, DSC is mainly used to measure the cure degree and glass transition temperature (Tg) of polymers used in the PCB. These two parameters determine PCB reliability during later process steps.

Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA)

TMA measures deformation behavior of solids, liquids, and gels under program-controlled temperature or mechanical force. It studies the link between thermal and mechanical behavior. From deformation vs. temperature (or time), you can study material physical and chemical properties and thermodynamics.

In PCB analysis, TMA mainly measures two key parameters: the coefficient of linear expansion and the glass transition temperature. If the base material has a large expansion coefficient, the PCB can often suffer metallized via fracture after soldering and assembly.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA measures the mass change of a substance under program-controlled temperature or time. With a precise balance, TGA can track small mass changes during a controlled temperature run.

From the mass change vs. temperature (or time) curve, you can study material physical and chemical behavior and thermodynamics. In PCB analysis, TGA is mainly used to measure the thermal stability or decomposition temperature of PCB materials. If a substrate has too-low decomposition temperature, the PCB will delaminate or crack during high-temperature soldering.

Final notes and best practice reminders

When you plan failure analysis, follow a clear, step-by-step approach. Start with visual and non-destructive checks. Use electrical tests and information collection. Then move to imaging methods like X-ray and SAM. If needed, use microchemical tools like micro-FTIR and surface imaging like SEM. Reserve destructive tests such as cross-sectioning for when you need microstructure information and when sample quantity allows destruction.

Always record data and keep clear facts. Use the simplest logical steps. Prove conclusions with experiments when possible. Do not change or damage the failure scene before you document it, because once the scene is altered, the true cause may be lost. Follow the rule: simple to complex, outside to inside, non-destructive to destructive. This saves time and yields correct analysis results.