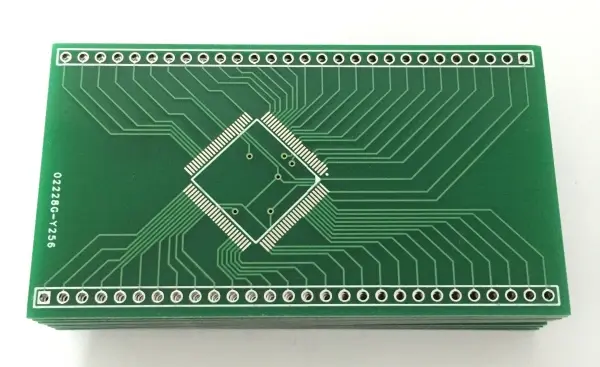

A single-sided PCB is the most basic printed circuit board. All parts sit on one side. All traces sit on the other side. Because only one side has traces, we call it a single-sided board. It is easy to make and it costs less. For that reason, simple electronic products often use single-sided PCBs.

When to use a double-sided PCB

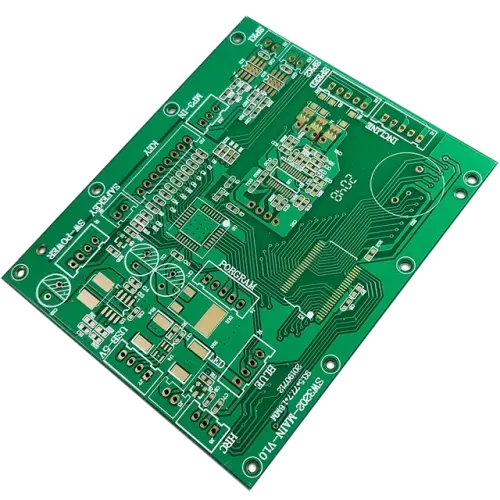

A double-sided PCB is a step up from a single-sided board. When one layer of routing cannot meet the needs of a product, designers use a double-sided board. Both sides have copper and traces. The two sides can connect with plated holes called vias. Vias let signals move from one layer to the other. That way the board can form the needed circuit network.

Similarities and differences between single-sided and double-sided PCBs

Materials and base process

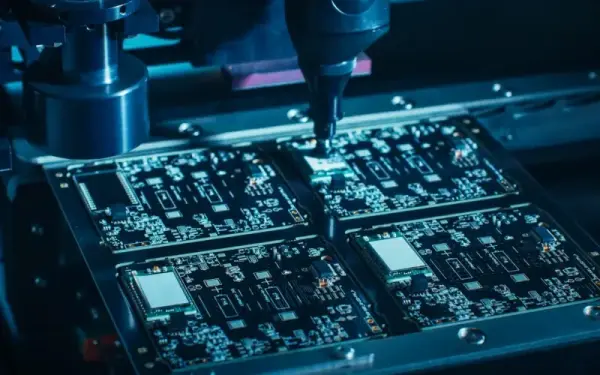

Single-sided and double-sided PCBs share the same basic material. Most modern boards use fr4. fr4 is a mix of glass fiber and epoxy. In modern making, we usually plate the board with copper for good conductivity. Then we add a solder mask for a neat look and for protection. A silkscreen or screen print adds labels and marks. Machines print the marks in a process called silkscreen.

Old manufacturing and limits

Modern board making was not always like this. In the past, engineers and hobbyists exposed designs on boards and then etched them by hand with chemical baths. Many methods existed. Most had the same limits. You could not etch many layers on one board easily. That forced layouts to be larger and to need heavy optimization.

In the 1960s this was fine. Large through-hole parts were the norm. Big rectangular chips had wide pins. These were DIP packages. Discrete through-hole parts like resistors and capacitors were large too. Parts laid close together so short traces were easy. That made single-sided layouts simple and clear.

The rise of surface-mount devices (SMD)

The 1980s changed the field. Surface-mount devices (SMD) became the preferred parts for engineers. Square flat packages grew common. SMD discrete parts made it hard to route under parts. Boards had to get smaller. Single-sided boards became harder to use. This pushed the growth of double-sided board techniques. With vias, you no longer had to keep all copper on the same side. You could route on both sides with plated holes that connect layers.

Double-sided printed circuit boards

Engineers moved to double-sided boards mainly for ease. When design limits force parts to a certain area, double-sided layouts are easier than single-sided ones. Double-sided boards also let you make large ground or power planes. If you look at a board closely, you may see large cuts of copper instead of many thin traces. These large copper zones help with EMI, heat, manufacturability, and most of all, they cut the routing work.

Why single-sided boards still exist

Even though double-sided boards have clear benefits, single-sided designs still appear in many products today. Cost is the main driver. Single-sided PCBs usually cost a little less to buy and sometimes have shorter lead times. For a simple design, that is a clear plus. In mass production of simple products, saving a few cents per board can matter a lot. Also, for high current traces that need wide copper, single-sided layouts can be a good fit. They let you use large copper areas and simple routing for heavy current paths.

Pros and cons of single-sided PCBs

Pros

Lower cost.

Simpler design and manufacture.

Shorter lead time in many cases.

Cons

Not good for complex designs with many parts.

Hard to meet small size needs.

Lower routing capacity.

Might be heavier and larger for the same function.

Typical applications of single-sided PCBs

Single-sided boards are common in many low-cost products. They appear in devices with simple functions that do not need large memory or network links. Examples include small home appliances like coffee machines. They also show up in many calculators, simple radios, printers, and LED lamps. Simple storage devices like basic solid-state drives may use single-sided boards. Power supplies and many kinds of sensors often use single-sided PCBs too.

How to tell single-sided, double-sided and multi-layer boards

Hold the board to a light. If the inner core is fully opaque and you cannot see light through inner layers, it is a multi-layer board. If you can see only one copper layer, it is a single-sided board.

Look at the holes. Single-sided boards have non-plated holes. They do not have plating on hole walls and they skip the electroplating process. Double-sided boards have plated through-holes or vias. That means you will see copper inside the hole.

The basic difference is the number of copper layers: single has one copper layer, double has two copper layers, and multi-layer has three layers or more. In multi-layer making, inner layers are added and then the stack is laminated. You can cut a cross-section to check layers if needed.

How to reduce EMI on single or double-sided PCBs

For cost reasons, many consumer devices use single or double-sided boards. As digital pulse circuits become common, EMI issues rise. The main cause is large signal loop area. Large loop areas not only emit stronger radiation, they also make the circuit more sensitive to outside noise. To improve EMC, the simplest approach is to reduce the loop area of critical signals.

Identify key signals

From an EMC view, key signals include those that make strong radiation and those that are sensitive to outside noise. Strong radiators are often periodic signals such as clocks and low-order address lines. Sensitive signals are often low-level analog lines.

Methods to reduce loop area

One simple method is to route a ground trace next to the signal trace. Put the ground as close as you can. That layout makes a very small loop area and cuts differential radiation and sensitivity. When you add a ground trace next to the signal, the signal current will mainly flow in that small loop, not in other ground paths.

If you use a double-sided board, place a ground trace on the other side right under the signal line. Make that ground trace wide if you can. The loop area then equals board thickness times the signal line length. That area is much smaller than a long open loop and helps cut radiation.

Also, always use a ground copper mesh on double-sided boards. A ground mesh lowers ground impedance. With a ground mesh, a signal line almost always has a ground line nearby and forms a smaller loop area. When routing, keep key lines close to ground. Only the most critical lines need a ground right next to them.

Other basic tips:

Use short traces for high-speed signals.

Use proper decoupling capacitors near power pins.

Keep analog and digital grounds separated and then join them at a single point if needed.

Avoid long loops. Route return paths near the signal path.

Small practical examples

For a clock trace on a double-sided board, put a wide ground trace under it on the other side. If the board thickness is 1.6 mm and the clock trace is 50 mm long, the loop area is roughly 1.6 mm × 50 mm. If you can shorten the trace to 20 mm, the area drops a lot.

For an analog signal that is sensitive, run a ground trace right beside it on the same side. Then the pair forms a tight loop and lowers pickup.

Sažetak

Single-sided PCBs are simple and cheap. They place all parts on one side and all traces on the other. Double-sided boards add a second layer and use vias to connect both sides. fr4 is the common material for both. The move from through-hole parts to surface-mount parts drove the need for double-sided and multi-layer boards. Yet single-sided boards still make sense for many simple products because of cost and ease. To lower EMI on single or double-sided boards, reduce loop area, add nearby ground traces, use ground mesh, and keep traces short.

Često postavljana pitanja

They are low cost, simple to design and manufacture, easy to test/repair, and ideal for large-volume, low-complexity products.

Yes—material and process complexity are lower, so unit cost and lead time are usually significantly less than for double-sided or multilayer PCBs.

Because components are on one side, plan part placement for reflow/wave soldering and ensure no obstructing components on the solder side; discuss solder process with your assembler.

Typical QA includes visual inspection, AOI (if applicable), electrical continuity/short tests, and functional testing when required by the customer.

Follow standard clearance and trace-width rules, route to minimize crossovers (since no second layer exists), and leave space for through-holes and pads—confirm fab DRC and minimums.